John Singer Sargent Giclée Fine Art Prints 1 of 10

1856-1925

American Impressionist Painter

The paradox of John Singer Sargent resides not merely in his technical brilliance - though that was formidable - but in his capacity to embody and transcend the contradictions of his era. Born in Florence on January 12, 1856, to American expatriates who had fled Philadelphia following family tragedy, Sargent emerged as perhaps the most accomplished portraitist of the Anglo-American world while remaining, in fundamental ways, perpetually displaced.

His father, FitzWilliam Sargent, had abandoned a promising career as an eye surgeon at Philadelphia's Wills Eye Hospital, acquiescing to his wife Mary's desire for European exile after the death of their first child. This nomadic existence, shuttling between Parisian apartments and Alpine retreats, Italian coastal towns and German spas, shaped young Sargent's sensibility in ways both profound and elusive. The family's deliberate avoidance of American society abroad created a curious vacuum in which the boy's artistic talents flourished unchecked by conventional expectations.

Mary Sargent's conviction that museums and churches could substitute for formal education proved both prescient and problematic. Her son emerged as a cosmopolitan polyglot - fluent in English, French, Italian, and German - yet his education remained fragmentary, assembled from encounters with art rather than systematic study. By thirteen, his mother noted his "remarkably quick and correct eye," though resources for proper instruction remained limited. The watercolor lessons he received from Carl Welsch, a minor German landscape painter, scarcely prepared him for what was to come.

The trajectory altered decisively in 1874 when Sargent, then eighteen, entered the Parisian atelier of Carolus-Duran. This choice proved revelatory. Carolus-Duran's rejection of traditional academic methods - the laborious drawing and underpainting that dominated École des Beaux-Arts instruction - in favor of direct painting alla prima, derived from Velázquez, liberated something essential in Sargent's temperament. His facility with the loaded brush, that capacity to capture form through tonal relationships rather than linear construction, would become his signature.

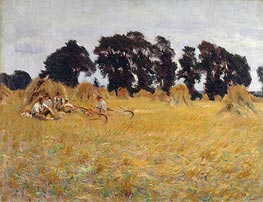

Yet Sargent's ambitions initially lay elsewhere. His early sketches reveal an obsession with landscape, architecture, the play of light on water and stone. Portrait painting represented a pragmatic concession to market realities rather than an aesthetic calling. The Salon system demanded it; commissions sustained it. His first major portrait, of Fanny Watts in 1877, demonstrated a precocious command of pose and atmosphere that announced his arrival.

The Spanish journey of 1879 crystallized Sargent's artistic identity. In Velázquez he discovered not merely technical precedent but a philosophical approach to representation - the conviction that surface could reveal essence without psychological excavation. This insight informed works like El Jaleo (1882), where Spanish dancers dissolve into rhythmic abstraction, gesture superseding individuality.

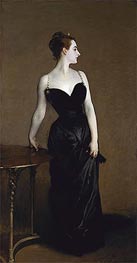

The catastrophe of Madame X (1884) - that portrait of Madame Pierre Gautreau with its notorious fallen shoulder strap - deserves reconsideration not as scandal but as aesthetic manifesto. Sargent's pursuit of the commission, his year-long struggle with the composition, his ultimate miscalculation of Parisian tolerance, reveal an artist testing boundaries he perhaps did not fully comprehend. The work's formal audacity - the alabaster profile against darkness, the reduction of femininity to serpentine contour - anticipated modernist simplifications while remaining rooted in nineteenth-century codes of beauty.

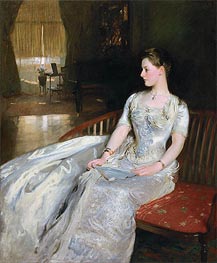

London offered refuge and transformation. Henry James, that other American exile, had urged the move; the Madame X debacle merely hastened it. English patronage proved more forgiving of Sargent's "Frenchified" handling, though critics initially resisted. His portrait practice evolved toward a peculiar synthesis - technical bravura wedded to psychological reticence. The subjects of his maturity possess an enigmatic quality, simultaneously revealed and withheld.

Consider Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (1887), painted in the Cotswolds garden of Broadway. The work's plein-air impressionism masks its artificiality - those Chinese lanterns relit evening after evening as summer waned, the child models growing visibly older as Sargent chased an ephemeral effect. Such dedication to capturing the momentary through obsessive repetition encapsulates his method's contradictions.

The American commissions of 1887-1888 established patterns that would persist. Isabella Stewart Gardner, Theodore Roosevelt, the Vanderbilt descendants - Sargent became chronicler of American privilege at its apogee. Yet these portraits, for all their material splendor, emanate a curious melancholy. The sitters inhabit their finery uneasily, as if aware of their historical moment's fragility.

By 1900, commanding fees of $5,000 per portrait, Sargent had achieved supreme technical mastery and social prominence. The Wertheimer family portraits, that extraordinary sequence documenting Jewish assimilation and anxiety, demonstrate his capacity to navigate cultural complexities through purely visual means. Yet satisfaction eluded him. His 1907 declaration - "Painting a portrait would be quite amusing if one were not forced to talk while working" - suggests profound weariness.

The post-1907 watercolors represent liberation rather than retreat. Freed from flattering wealthy sitters, Sargent pursued light and movement with renewed urgency. The Venetian studies, Bedouin encampments, Alpine streams - these works pulse with immediacy absent from the late portraits. In them, one glimpses what Sargent might have achieved had economic necessity not dictated his course.

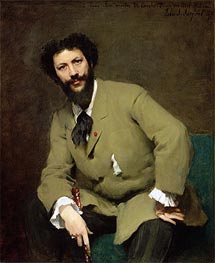

Recent scholarship has complicated our understanding of Sargent's personal life, particularly regarding his sexuality. The reemergence of his male nudes, the intensity of certain male portraits, his lifelong bachelorhood, and contemporary accounts suggest a complexity deliberately obscured. His relationship with Albert de Belleroche, the androgynous beauty of many subjects regardless of gender, the very theatricality of his social persona - all point toward carefully managed difference.

The Boston Public Library murals, that three-decade project left incomplete at his death in 1925, epitomize both ambition and limitation. The attempted synthesis of religious traditions through aesthetic means, culminating in the controversial "Synagogue" and "Church" panels, revealed an artist struggling with content beyond his essentially formal intelligence. His genuine bewilderment at Jewish objections to his stereotypical iconography suggests an aesthete's dangerous innocence.

Sargent died at his Chelsea home on April 14, 1925, having witnessed his reputation's decline among modernist critics. Roger Fry's dismissal - "most wonderful that this wonderful performance should ever have been confused with that of an artist" - typified avant-garde rejection of his achievement. Yet this judgment itself demands scrutiny. In reducing painting to performance, in privileging surface over depth, did not Sargent anticipate postmodern strategies? His best work suggests that virtuosity need not preclude meaning, that the gesture of representation might constitute its own form of truth.

His father, FitzWilliam Sargent, had abandoned a promising career as an eye surgeon at Philadelphia's Wills Eye Hospital, acquiescing to his wife Mary's desire for European exile after the death of their first child. This nomadic existence, shuttling between Parisian apartments and Alpine retreats, Italian coastal towns and German spas, shaped young Sargent's sensibility in ways both profound and elusive. The family's deliberate avoidance of American society abroad created a curious vacuum in which the boy's artistic talents flourished unchecked by conventional expectations.

Mary Sargent's conviction that museums and churches could substitute for formal education proved both prescient and problematic. Her son emerged as a cosmopolitan polyglot - fluent in English, French, Italian, and German - yet his education remained fragmentary, assembled from encounters with art rather than systematic study. By thirteen, his mother noted his "remarkably quick and correct eye," though resources for proper instruction remained limited. The watercolor lessons he received from Carl Welsch, a minor German landscape painter, scarcely prepared him for what was to come.

The trajectory altered decisively in 1874 when Sargent, then eighteen, entered the Parisian atelier of Carolus-Duran. This choice proved revelatory. Carolus-Duran's rejection of traditional academic methods - the laborious drawing and underpainting that dominated École des Beaux-Arts instruction - in favor of direct painting alla prima, derived from Velázquez, liberated something essential in Sargent's temperament. His facility with the loaded brush, that capacity to capture form through tonal relationships rather than linear construction, would become his signature.

Yet Sargent's ambitions initially lay elsewhere. His early sketches reveal an obsession with landscape, architecture, the play of light on water and stone. Portrait painting represented a pragmatic concession to market realities rather than an aesthetic calling. The Salon system demanded it; commissions sustained it. His first major portrait, of Fanny Watts in 1877, demonstrated a precocious command of pose and atmosphere that announced his arrival.

The Spanish journey of 1879 crystallized Sargent's artistic identity. In Velázquez he discovered not merely technical precedent but a philosophical approach to representation - the conviction that surface could reveal essence without psychological excavation. This insight informed works like El Jaleo (1882), where Spanish dancers dissolve into rhythmic abstraction, gesture superseding individuality.

The catastrophe of Madame X (1884) - that portrait of Madame Pierre Gautreau with its notorious fallen shoulder strap - deserves reconsideration not as scandal but as aesthetic manifesto. Sargent's pursuit of the commission, his year-long struggle with the composition, his ultimate miscalculation of Parisian tolerance, reveal an artist testing boundaries he perhaps did not fully comprehend. The work's formal audacity - the alabaster profile against darkness, the reduction of femininity to serpentine contour - anticipated modernist simplifications while remaining rooted in nineteenth-century codes of beauty.

London offered refuge and transformation. Henry James, that other American exile, had urged the move; the Madame X debacle merely hastened it. English patronage proved more forgiving of Sargent's "Frenchified" handling, though critics initially resisted. His portrait practice evolved toward a peculiar synthesis - technical bravura wedded to psychological reticence. The subjects of his maturity possess an enigmatic quality, simultaneously revealed and withheld.

Consider Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (1887), painted in the Cotswolds garden of Broadway. The work's plein-air impressionism masks its artificiality - those Chinese lanterns relit evening after evening as summer waned, the child models growing visibly older as Sargent chased an ephemeral effect. Such dedication to capturing the momentary through obsessive repetition encapsulates his method's contradictions.

The American commissions of 1887-1888 established patterns that would persist. Isabella Stewart Gardner, Theodore Roosevelt, the Vanderbilt descendants - Sargent became chronicler of American privilege at its apogee. Yet these portraits, for all their material splendor, emanate a curious melancholy. The sitters inhabit their finery uneasily, as if aware of their historical moment's fragility.

By 1900, commanding fees of $5,000 per portrait, Sargent had achieved supreme technical mastery and social prominence. The Wertheimer family portraits, that extraordinary sequence documenting Jewish assimilation and anxiety, demonstrate his capacity to navigate cultural complexities through purely visual means. Yet satisfaction eluded him. His 1907 declaration - "Painting a portrait would be quite amusing if one were not forced to talk while working" - suggests profound weariness.

The post-1907 watercolors represent liberation rather than retreat. Freed from flattering wealthy sitters, Sargent pursued light and movement with renewed urgency. The Venetian studies, Bedouin encampments, Alpine streams - these works pulse with immediacy absent from the late portraits. In them, one glimpses what Sargent might have achieved had economic necessity not dictated his course.

Recent scholarship has complicated our understanding of Sargent's personal life, particularly regarding his sexuality. The reemergence of his male nudes, the intensity of certain male portraits, his lifelong bachelorhood, and contemporary accounts suggest a complexity deliberately obscured. His relationship with Albert de Belleroche, the androgynous beauty of many subjects regardless of gender, the very theatricality of his social persona - all point toward carefully managed difference.

The Boston Public Library murals, that three-decade project left incomplete at his death in 1925, epitomize both ambition and limitation. The attempted synthesis of religious traditions through aesthetic means, culminating in the controversial "Synagogue" and "Church" panels, revealed an artist struggling with content beyond his essentially formal intelligence. His genuine bewilderment at Jewish objections to his stereotypical iconography suggests an aesthete's dangerous innocence.

Sargent died at his Chelsea home on April 14, 1925, having witnessed his reputation's decline among modernist critics. Roger Fry's dismissal - "most wonderful that this wonderful performance should ever have been confused with that of an artist" - typified avant-garde rejection of his achievement. Yet this judgment itself demands scrutiny. In reducing painting to performance, in privileging surface over depth, did not Sargent anticipate postmodern strategies? His best work suggests that virtuosity need not preclude meaning, that the gesture of representation might constitute its own form of truth.

230 Sargent Artworks

Page 1 of 10

Giclée Canvas Print

$62.05

$62.05

SKU: 1711-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:139 x 90.6 cm

The Clark Art Institute, Massachusetts, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:139 x 90.6 cm

The Clark Art Institute, Massachusetts, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$83.10

$83.10

SKU: 1731-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:174 x 153.7 cm

Tate Gallery, London, UK

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:174 x 153.7 cm

Tate Gallery, London, UK

Giclée Canvas Print

$66.59

$66.59

SKU: 1730-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:54 x 64.8 cm

Tate Gallery, London, UK

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:54 x 64.8 cm

Tate Gallery, London, UK

Giclée Canvas Print

$62.05

$62.05

SKU: 15245-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:101 x 59.4 cm

Seattle Art Museum, Washington, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:101 x 59.4 cm

Seattle Art Museum, Washington, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$73.35

$73.35

SKU: 1776-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:55.9 x 71.1 cm

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:55.9 x 71.1 cm

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, USA

Giclée Paper Art Print

$58.76

$58.76

SKU: 15203-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:34.3 x 52.7 cm

Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:34.3 x 52.7 cm

Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$73.19

$73.19

SKU: 15373-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:56.5 x 71.7 cm

Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:56.5 x 71.7 cm

Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$62.05

$62.05

SKU: 15392-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:204.5 x 111.6 cm

Private Collection

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:204.5 x 111.6 cm

Private Collection

Giclée Canvas Print

$71.13

$71.13

SKU: 15260-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:93 x 71 cm

Private Collection

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:93 x 71 cm

Private Collection

Giclée Canvas Print

$72.15

$72.15

SKU: 15186-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:71 x 91.4 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:71 x 91.4 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$62.05

$62.05

SKU: 1720-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:208.6 x 110 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:208.6 x 110 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$78.65

$78.65

SKU: 1773-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:63.8 x 76.2 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:63.8 x 76.2 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$62.05

$62.05

SKU: 15345-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:unknown

Public Collection

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:unknown

Public Collection

Giclée Canvas Print

$70.10

$70.10

SKU: 15206-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:71 x 53.3 cm

Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:71 x 53.3 cm

Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$73.87

$73.87

SKU: 15381-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:55.2 x 69.8 cm

Tate Gallery, London, UK

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:55.2 x 69.8 cm

Tate Gallery, London, UK

Giclée Canvas Print

$62.75

$62.75

SKU: 1721-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:232 x 348 cm

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:232 x 348 cm

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$86.97

$86.97

SKU: 1781-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:205.7 x 115.6 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:205.7 x 115.6 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$77.63

$77.63

SKU: 15274-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:167.6 x 137.8 cm

Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:167.6 x 137.8 cm

Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$76.43

$76.43

SKU: 15237-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:61.3 x 50.2 cm

Dallas Museum of Art, Texas, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:61.3 x 50.2 cm

Dallas Museum of Art, Texas, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$76.60

$76.60

SKU: 1780-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:125.4 x 102.8 cm

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:125.4 x 102.8 cm

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$82.11

$82.11

SKU: 15173-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:213.4 x 113.7 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:213.4 x 113.7 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$62.05

$62.05

SKU: 1703-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:78.7 x 123 cm

Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:78.7 x 123 cm

Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$77.46

$77.46

SKU: 1708-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:116.8 x 96 cm

The Clark Art Institute, Massachusetts, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:116.8 x 96 cm

The Clark Art Institute, Massachusetts, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$68.40

$68.40

SKU: 1751-SAR

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:292.1 x 213.7 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

John Singer Sargent

Original Size:292.1 x 213.7 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA