Hieronymus Bosch Giclée Fine Art Prints

c.1450-1516

Netherlandish Northern Renaissance Painter

The paradox of Hieronymus Bosch lies not merely in the fantastical visions that emerged from his workshop, but in the prosaic documentary trail he left behind - municipal records, brotherhood accounts, property transactions. Born Jheronimus van Aken around 1450, the artist we know as Bosch derived his working name from 's-Hertogenbosch, the Brabantine town where he spent his entire life. This geographical rootedness stands in marked contrast to the otherworldly landscapes he conjured, suggesting an imagination that found its most profound expression precisely through its containment within familiar boundaries.

The van Aken family had established itself in the artistic life of 's-Hertogenbosch through several generations. His grandfather Jan, recorded as a painter in 1430, produced five sons, four of whom followed the paternal profession. Bosch's father, Anthonius, served as artistic adviser to the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady, a position that implies both technical competence and social standing. Yet no works survive from these earlier generations - a silence that makes Bosch's eventual achievement appear almost sui generis, though we must assume the fundamental craftsmanship was transmitted through traditional workshop practices.

The catastrophic fire of 1463 that destroyed four thousand houses in 's-Hertogenbosch occurred when Bosch was approximately thirteen - an age when such devastation would leave indelible impressions. Whether this early exposure to urban apocalypse influenced his later depictions of conflagration and chaos remains speculation, yet the timing seems more than coincidental. The reconstruction that followed would have provided abundant work for artists and craftsmen, possibly accelerating young Jheronimus's professional development.

His marriage between 1479 and 1481 to Aleid Goyaerts van den Meervenne represented both personal and economic advancement. She brought property in nearby Oirschot and came from substantial means - a union that freed Bosch from the financial pressures that constrained many contemporary artists. This economic security perhaps enabled the artistic risks and innovations that distinguish his mature work. The couple remained childless, a biographical detail that some scholars have connected, perhaps too facilely, to the artist's apparent fascination with corruption and regeneration.

Bosch's admission to the Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady in 1486-87 marked his full integration into the town's religious and social elite. This confraternity, numbering forty local members and thousands of external affiliates across Europe, provided both spiritual community and potential patronage networks. The Brotherhood's records offer our most reliable chronological framework for Bosch's life, including the notice of his death and the funeral mass held on August 9, 1516.

The technical aspects of Bosch's practice reveal a methodical craftsman beneath the visionary surface. Working primarily on oak panels with oil medium, he employed a relatively restricted palette - azurite for celestial and distant effects, copper-based greens for vegetation, lead-tin-yellow, ochres, and red lakes for figures. His painting technique, however, departed from Netherlandish conventions. Where contemporaries pursued smooth surfaces through multiple transparent glazes, Bosch often worked in a comparatively rough manner, allowing brushwork and impasto effects to remain visible. This technical choice - whether driven by temperament, efficiency, or aesthetic preference - contributed to the sense of urgent revelation in his imagery.

The chronology of Bosch's artistic development remains contentious, though recent dendrochronological analysis of his oak panels has provided firmer dating. The traditional division into early (c.1470-1485), middle (c.1485-1500), and late (c.1500-1516) periods serves organizational purposes while acknowledging the speculative nature of such periodization. What emerges clearly is an artist who maintained a productive workshop - evidenced by pupils and numerous copies - while developing an increasingly complex symbolic vocabulary.

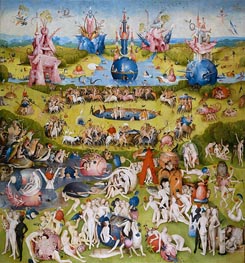

The acquisition of many Bosch paintings by Philip II of Spain in the late sixteenth century ensured both their preservation and their removal from their original context. The concentration of works in the Prado - including The Garden of Earthly Delights, The Haywain Triptych, and The Seven Deadly Sins - has shaped subsequent reception, creating an Iberian lens through which much Bosch scholarship has necessarily operated.

Contemporary interpretation of Bosch has oscillated between extremes. The twentieth-century tendency to read heretical or hermetic meanings into his work - connecting him to Cathars, Adamites, or alchemical traditions - has largely given way to readings that emphasize his orthodox religious context. His imagery, however disturbing or fantastic, aligns with late medieval moralizing literature and sermon traditions. The recent emphasis on ironic elements in his work suggests a sophistication that appealed simultaneously to conservative and progressive sensibilities - a strategic ambiguity that may have been quite deliberate.

The attribution debates surrounding Bosch's oeuvre reflect broader methodological shifts in art history. From the expansive attributions of mid-twentieth century scholars like Tolnay and Baldass - who credited him with thirty to fifty works - the authenticated corpus has contracted significantly. Current consensus recognizes approximately twenty-five paintings as autograph works, with another half-dozen assigned to his workshop. The 2016 reattribution of The Temptation of St. Anthony from workshop to autograph status demonstrates how technical analysis continues to reshape the catalogue, while the simultaneous demotion of other works reminds us that the Bosch we study remains partially a construction of scholarly consensus.

What emerges from the documentary fragments and material evidence is an artist firmly embedded in his provincial milieu who nonetheless achieved a visual language of universal resonance. The tension between Bosch's conventional life trajectory - successful craftsman, prosperous marriage, civic respectability - and his extraordinary imaginative productions suggests not contradiction but synthesis. Perhaps it was precisely his secure position within traditional structures that enabled such radical reimagining of spiritual and moral themes. In Bosch, we encounter not the outsider artist of Romantic mythology but something more unsettling: the respectable burgher whose inner vision encompassed both paradise and pandemonium.

The van Aken family had established itself in the artistic life of 's-Hertogenbosch through several generations. His grandfather Jan, recorded as a painter in 1430, produced five sons, four of whom followed the paternal profession. Bosch's father, Anthonius, served as artistic adviser to the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady, a position that implies both technical competence and social standing. Yet no works survive from these earlier generations - a silence that makes Bosch's eventual achievement appear almost sui generis, though we must assume the fundamental craftsmanship was transmitted through traditional workshop practices.

The catastrophic fire of 1463 that destroyed four thousand houses in 's-Hertogenbosch occurred when Bosch was approximately thirteen - an age when such devastation would leave indelible impressions. Whether this early exposure to urban apocalypse influenced his later depictions of conflagration and chaos remains speculation, yet the timing seems more than coincidental. The reconstruction that followed would have provided abundant work for artists and craftsmen, possibly accelerating young Jheronimus's professional development.

His marriage between 1479 and 1481 to Aleid Goyaerts van den Meervenne represented both personal and economic advancement. She brought property in nearby Oirschot and came from substantial means - a union that freed Bosch from the financial pressures that constrained many contemporary artists. This economic security perhaps enabled the artistic risks and innovations that distinguish his mature work. The couple remained childless, a biographical detail that some scholars have connected, perhaps too facilely, to the artist's apparent fascination with corruption and regeneration.

Bosch's admission to the Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady in 1486-87 marked his full integration into the town's religious and social elite. This confraternity, numbering forty local members and thousands of external affiliates across Europe, provided both spiritual community and potential patronage networks. The Brotherhood's records offer our most reliable chronological framework for Bosch's life, including the notice of his death and the funeral mass held on August 9, 1516.

The technical aspects of Bosch's practice reveal a methodical craftsman beneath the visionary surface. Working primarily on oak panels with oil medium, he employed a relatively restricted palette - azurite for celestial and distant effects, copper-based greens for vegetation, lead-tin-yellow, ochres, and red lakes for figures. His painting technique, however, departed from Netherlandish conventions. Where contemporaries pursued smooth surfaces through multiple transparent glazes, Bosch often worked in a comparatively rough manner, allowing brushwork and impasto effects to remain visible. This technical choice - whether driven by temperament, efficiency, or aesthetic preference - contributed to the sense of urgent revelation in his imagery.

The chronology of Bosch's artistic development remains contentious, though recent dendrochronological analysis of his oak panels has provided firmer dating. The traditional division into early (c.1470-1485), middle (c.1485-1500), and late (c.1500-1516) periods serves organizational purposes while acknowledging the speculative nature of such periodization. What emerges clearly is an artist who maintained a productive workshop - evidenced by pupils and numerous copies - while developing an increasingly complex symbolic vocabulary.

The acquisition of many Bosch paintings by Philip II of Spain in the late sixteenth century ensured both their preservation and their removal from their original context. The concentration of works in the Prado - including The Garden of Earthly Delights, The Haywain Triptych, and The Seven Deadly Sins - has shaped subsequent reception, creating an Iberian lens through which much Bosch scholarship has necessarily operated.

Contemporary interpretation of Bosch has oscillated between extremes. The twentieth-century tendency to read heretical or hermetic meanings into his work - connecting him to Cathars, Adamites, or alchemical traditions - has largely given way to readings that emphasize his orthodox religious context. His imagery, however disturbing or fantastic, aligns with late medieval moralizing literature and sermon traditions. The recent emphasis on ironic elements in his work suggests a sophistication that appealed simultaneously to conservative and progressive sensibilities - a strategic ambiguity that may have been quite deliberate.

The attribution debates surrounding Bosch's oeuvre reflect broader methodological shifts in art history. From the expansive attributions of mid-twentieth century scholars like Tolnay and Baldass - who credited him with thirty to fifty works - the authenticated corpus has contracted significantly. Current consensus recognizes approximately twenty-five paintings as autograph works, with another half-dozen assigned to his workshop. The 2016 reattribution of The Temptation of St. Anthony from workshop to autograph status demonstrates how technical analysis continues to reshape the catalogue, while the simultaneous demotion of other works reminds us that the Bosch we study remains partially a construction of scholarly consensus.

What emerges from the documentary fragments and material evidence is an artist firmly embedded in his provincial milieu who nonetheless achieved a visual language of universal resonance. The tension between Bosch's conventional life trajectory - successful craftsman, prosperous marriage, civic respectability - and his extraordinary imaginative productions suggests not contradiction but synthesis. Perhaps it was precisely his secure position within traditional structures that enabled such radical reimagining of spiritual and moral themes. In Bosch, we encounter not the outsider artist of Romantic mythology but something more unsettling: the respectable burgher whose inner vision encompassed both paradise and pandemonium.

6 Hieronymus Bosch Artworks

Giclée Canvas Print

$92.25

$92.25

SKU: 16869-BHE

Hieronymus Bosch

Original Size:183 x 171 cm

Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

Hieronymus Bosch

Original Size:183 x 171 cm

Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

Giclée Canvas Print

$65.51

$65.51

SKU: 16868-BHE

Hieronymus Bosch

Original Size:183 x 76 cm

Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

Hieronymus Bosch

Original Size:183 x 76 cm

Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

Giclée Canvas Print

$65.51

$65.51

SKU: 16867-BHE

Hieronymus Bosch

Original Size:183 x 76 cm

Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

Hieronymus Bosch

Original Size:183 x 76 cm

Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

Giclée Canvas Print

$65.51

$65.51

SKU: 16865-BHE

Hieronymus Bosch

Original Size:136 x 46 cm

Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

Hieronymus Bosch

Original Size:136 x 46 cm

Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

Giclée Canvas Print

$73.29

$73.29

SKU: 16866-BHE

Hieronymus Bosch

Original Size:136 x 101 cm

Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

Hieronymus Bosch

Original Size:136 x 101 cm

Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

Giclée Canvas Print

$65.51

$65.51

SKU: 16864-BHE

Hieronymus Bosch

Original Size:136 x 46 cm

Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

Hieronymus Bosch

Original Size:136 x 46 cm

Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain